In the last few years, I’ve fallen in love with both the lap steel guitar, and with alternate microtonal tunings like 22 equal divisions of the octave. I think enthusiasts in both steel guitar and xenharmonic worlds have a lot in common. And, I think the lap steel guitar offers a very approachable entrypoint into xenharmonic music. So, I am working to develop tuning approaches for lap steel guitars that support alternate tuning systems.

Though I am not an expert either in xenharmonic theory or in lap steel guitar technique, I understand enough about each topic to theorize and daydream about how one could approach a combination of the two. Here I would like to offer one or two guitar tunings that folks can use to explore harmonies and melodies in 22EDO on a lap steel guitar.

On a lap steel guitar, strings are tuned to an open chord that provides players with an assortment of the most useful intervals and chords for a particular style or need. Frets are visual guides, and too far from strings to touch them. To play a desired note or chord, players move a heavy bar, usually steel, up and down the fretboard, keeping it perpendicular to the strings.

To quote someone from the steel guitar community, there are as many (if not more) lap steel tunings as there are lap steel players. Different steel tunings are better for different styles (like Hawaiian music, vs. Western Swing, vs. Indian Classical).

To access some intervals, the bar can be slanted forwards or backwards so that it lines up with different strings on different frets. For example, if string 1 and string 4 are a minor sixth apart, a player can slant the bar forward by one fret to play a major sixth. It’s also possible to line up 3 or more strings along a slanted bar, but keeping all the notes in tune is pretty challenging - it’s hard enough just with two notes involved. In any case, I think slants could be a very useful technique when playing in xenharmonic tunings.

Note that pedal steel guitars are similar to lap steels, but their added foot pedals and knee levers offer countless possible ways to raise or lower a string’s pitch. These young instruments are fascinating and they make beautiful music. They’re also mechanically complex, and my understanding is that it’s quite difficult for players to become proficient. They are also expensive, so I can’t consider them as an entry point. I hope that pedal steel players will find an interest in xenharmonics, but so far I haven’t run across any such musicians. I’ll continue focusing on lap steel guitars for their simplicity and accessibility.

Most of the music we know in the “Western” tradition uses twelve notes per octave, or 12EDO. In this tuning, a C sharp is equivalent to a D flat, and all of the semitones are of equal size. The octave is divided equally into 12 semitones or halfsteps, and we say that each semitone has a size of 100 cents. Measuring in cents helps us with fine-tuning, so we can describe, among other things, how far out of tune a note might be.

22EDO, then, is a tuning system that divides the octave into 22 equal pieces instead of 12. These pieces are a little more than half the size of our normal semitones (54.5 cents). On a stereotypical guitar (not a lap steel), let’s imagine having 22 frets per octave instead of 12. We’ll keep the same string tuning for now. What happens if we try to use our familiar 12-EDO chord shapes and scale patterns? Well, ignoring some extra buzzing, we can imagine that our fingers will find the nearest matching notes this strange fretboard has to offer. We’ll notice that some notes sound really close to the pitches we expect, while others aren’t as close.

In 22EDO, we have lots of familiar intervals under our fingers, plus some new exotic ones that offer more nuance, both melodically and harmonically. By the way, the word ‘exotic’ is terribly overused in discussions about tuning theory; I hope you don’t mind that I‘m just rolling with it. Here are some basic observations about 22EDO:

One of the more versatile tunings for traditional lap steel is the C6 tuning, which provides a major triad, a minor triad, and other 2 or 3-note chords that can imply lots of other harmonies. It’s also possibly the most popular tuning, and the first one many will learn. C6 tuning, from low to high, is C,E,G,A,C,E. Variations like A6 keep the same relationship between the strings, and transpose them all up or down by the same amount. In my tunings, I try to use the C6 as a model as much as possible.

To tune a six-string instrument for 22EDO, a player can keep the same set of strings and detune them as follows: A,vC#,E,G,B,D. vC# is down-csharp. Using ‘A’ as the reference tone/root, the strings would have the following intervals, in edosteps: 0, 7,13,18,26,31. Measured in cents, this is 0, 381.8, 709.1, 981.9, 1418.2, 1690.9.

An alternative could be A,vC#,E,G,A,vC#. This offers octaves on the root and downmajor third of the chord, which may be more useful for melodic playing. However, this doesn’t provide as many unique intervals as the first suggested tuning. It is very close to the familiar and beloved A6 guitar tuning, so it may be the easiest entrypoint for lap steel players.

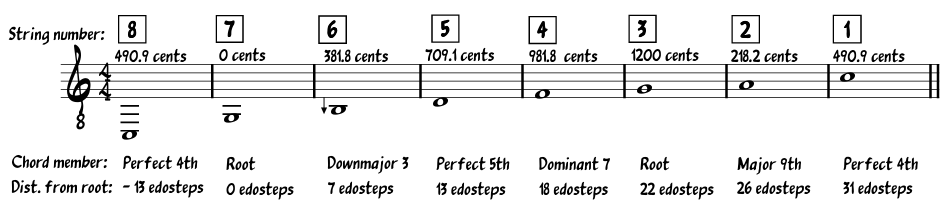

I have spent most of my time so far with a long-scale eight-string guitar tuned as follows, from low to high: C,G,vB,D,F,G,A,C.

In this tuning the reference pitch and root is G. Here are some important features of the guitar tuning:

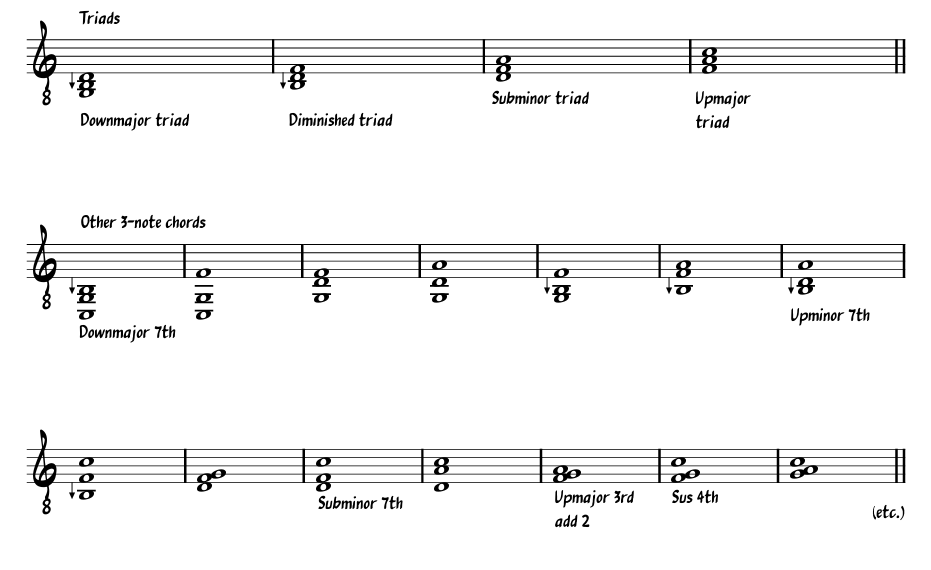

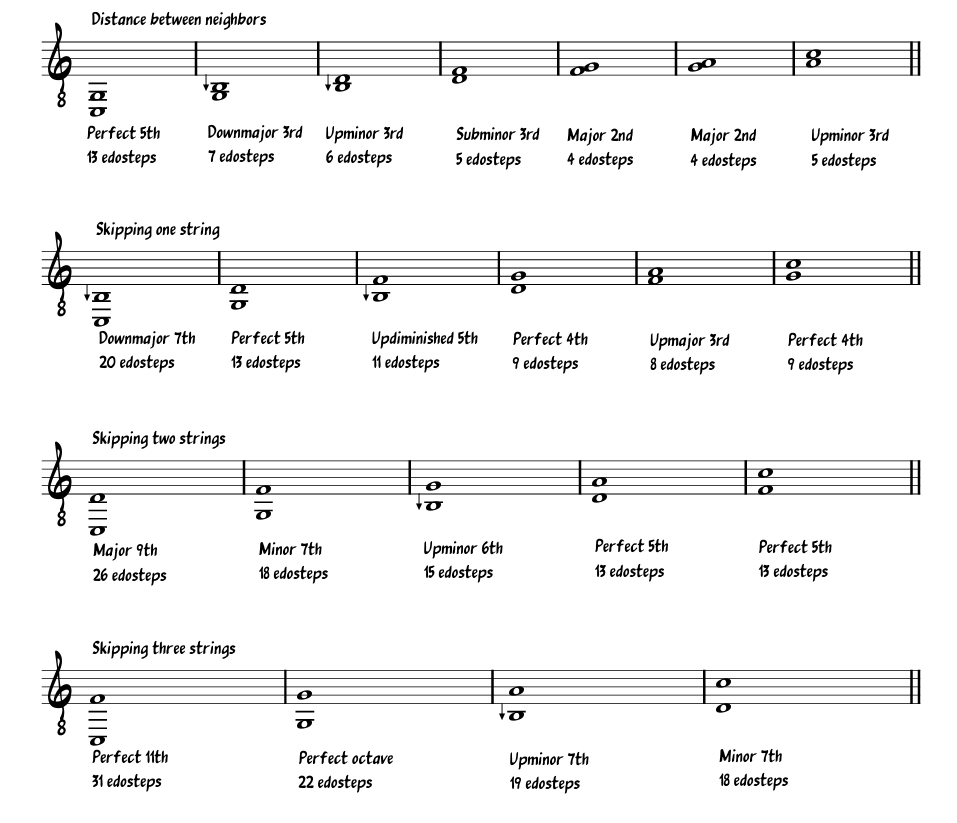

These chord qualities are readily available:

These two-note intervals are available as well:

Using a slant, a player could also access many of the intervals missing from the list above (an upfourth, which is 10 edosteps for example).

I built my 8-string guitar to have a 30-inch scale length, which is much longer than most steel or traditional guitars. This spreads out the frets quite a lot, and I think it makes it much easier to find your target pitch. It also allows for more nuance since the movements of your slide don’t change pitch quite as much. The tradeoff is perhaps a little less dexterity when your notes are towards the far end of the neck, but I think it’s definitely worth it.

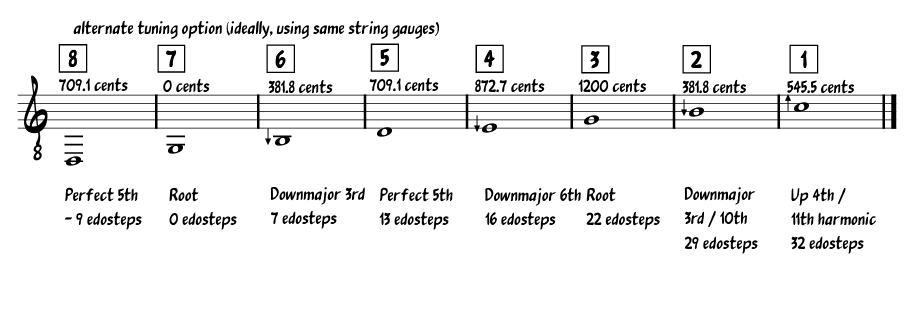

Here is a slight modification of the lap steel tuning that's worth considering as well. It's more similar to G6 lap steel tuning, with the 11th harmonic added on the top string and the fifth added to the lowest string. There aren't as many different kinds of intervals available in each bar position. But I think it may be a little easier to grok, especially for steel players that have some familiarity with a 'sixth' tuning.

This is one of my favorite things about steel guitar, aside from the bends, glisses, harmonic exploration, etc. Using the fretfind tool at ekips.org, you can print out a fretboard on your printer. Here are the steps I recommend following:

Use a pencil to add any landmarks or guides that you like. I will usually draw in some fret inlay dots as near as possible to traditional guitar inlay positions. First, I like to number each fret, starting with zero. The octave fret will be at the fret number that matches the EDO. For 22EDO, I add the inlay dots between these frets:

Notice that for 22EDO, the inlay dots are not spaced equally. The first dot is 5 frets away from zero, and the second, third and fourth dots are 4 frets above from their downstream neighbors. Then, the octave dot is 5 frets away from the 4th. The pattern that emerges is: subminor 3rd, whole step, whole step whole step, subminor 3rd, repeat. On a traditional fretboard, the pattern would be similar: minor 3rd, whole step, whole step, whole step, minor 3rd, minor 3rd, whole step, whole step, whole step, minor 3rd.

I also like to darken the fret lines above the dots with pencil. You might experiment with adding other landmarks to help you differentiate frets. This is the beauty of using pencil and paper.

Cut your pages out along the gray lines. Any fret lines you see outside the gray lines are duplicated on the neighboring page, and you can use them to align the pages. Once I’ve cut them out, I use either masking tape to attach the pages to each other. Then I will attach them to the guitar either with masking tape or double-sided tape.

NOTE! Watch out for using tape on certain surfaces. I can’t offer a whole lot of guidance on this because I use cheap and DIY instruments that don’t mind tape. On your instrument there may be decals or finishes that don’t like to be taped and will peel away with the tape. My best advice is to avoid glossy finish, inlays, or anything that you’re not sure should be taped to.